AI agent sandboxing in 2026: how to choose between primitives, runtimes, and platforms

Why AI agent sandboxing changed in 2026

Look, engineering leaders in 2026 have too many choices. And honestly, that didn’t exist three years ago.

We’ve moved way past the “Containers vs. VMs” debate. Now you’re staring at Firecracker MicroVMs, gVisor user-space kernels, Cloud Hypervisor, WebAssembly isolates, and emerging Library OS tech like Microsoft’s LiteBox. It’s kind of overwhelming.

But this isn’t just vendors making noise. This proliferation is the industry’s response to a real problem: standard multi-tenant containers can’t safely contain AI agents executing arbitrary code.

Think about it. When an agent can write its own Python scripts, install packages, and manipulate file descriptors, the shared kernel surface area of a standard Docker container becomes a liability. Major cloud providers, including AWS, Azure, and GCP, have all quietly migrated their control planes away from runc toward hardware-enforced isolation.

This guide maps the 2026 sandbox ecosystem structurally. We’re not comparing tools in isolation. Instead, we’re defining the architectural layers. If you’re a Series A+ engineering leader who’s outgrown “Docker on EC2” and needs a security posture that survives a red team audit without blowing your engineering budget, keep reading.

Executive summary: AI agent sandboxing in 2026

As of February 2026, the consensus is clear: shared-kernel container isolation (Docker/runc) isn’t cutting it anymore for executing untrusted AI agent code. You need to treat LLM-generated or user-supplied code as hostile. A shared kernel just expands the blast radius.

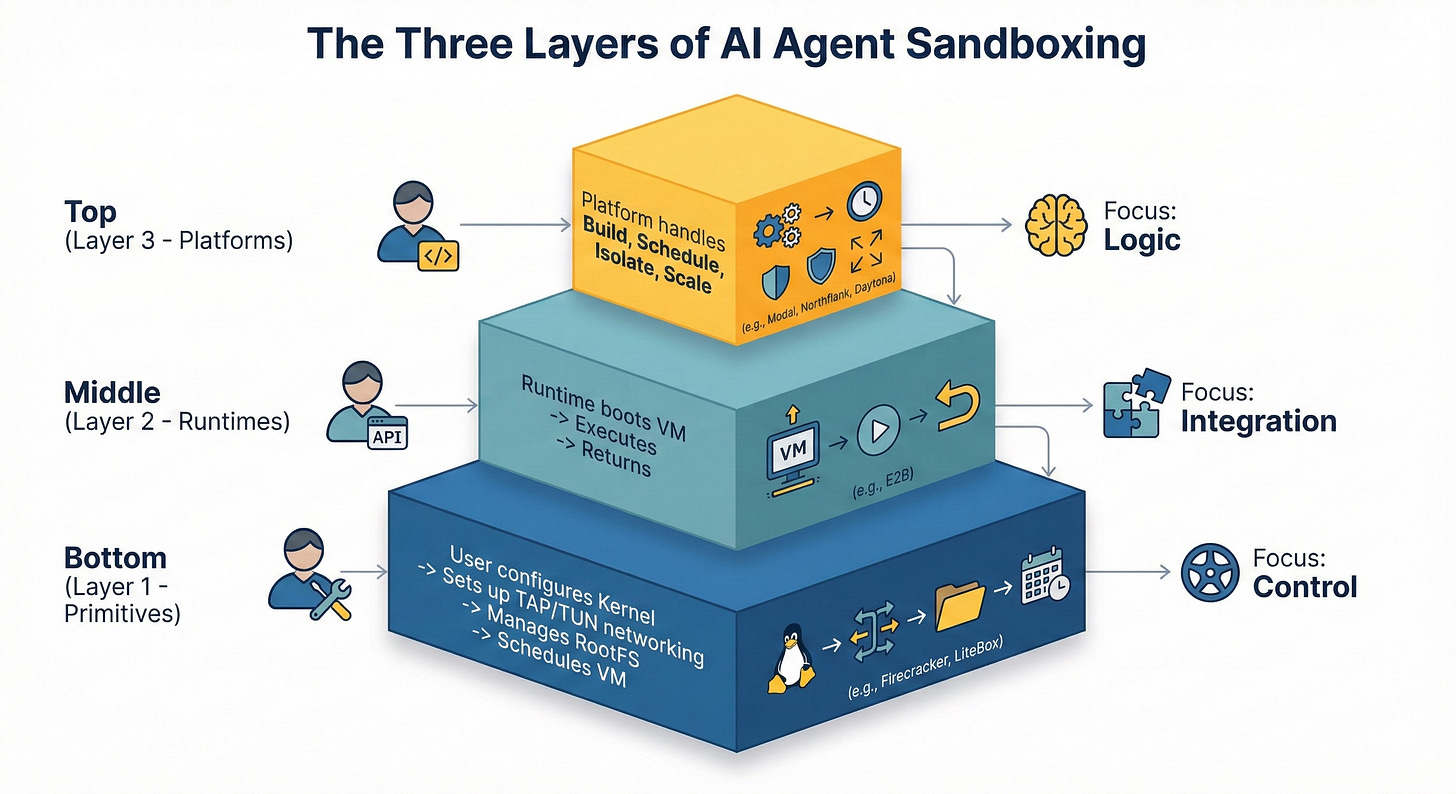

The market has split into three layers:

Primitives (Firecracker/gVisor/LiteBox): Best for teams willing to run their own fleet and scheduler for maximum control.

Embeddable runtimes (E2B, microsandbox): Best for quickly adding code execution — managed API (E2B) or self-hosted (microsandbox).

Managed platforms (Daytona, Modal, Northflank): Best for data-heavy workloads, GPU access, or zero-ops scaling — but each with different isolation, pricing, and lock-in tradeoffs.

Hybrid (Google Agent Sandbox): Best for teams already on Kubernetes who want open-source sandboxing with warm pools and no new vendor dependency.

Pick Layer 1 when you need maximum control and customization for compliance. Pick Layer 2 when you want the fastest path to ephemeral code execution with strong isolation. Pick Layer 3 when you need GPUs, data-local execution, or zero-ops scaling — but evaluate vendor lock-in, language constraints, and BYOC support carefully.

The isolation spectrum: five levels of sandbox security

Before choosing a tool, understand the five isolation levels available in 2026. Each step up trades performance overhead for a stronger security boundary.

Level 1: Containers (Docker, Podman) Processes share the host kernel, separated by Linux namespaces and cgroups. Fast and lightweight, but a kernel vulnerability in one container can compromise all others. Sufficient for trusted, internally-written code. Insufficient for anything an LLM generates.

Level 2: User-space kernels (gVisor) A user-space application intercepts and re-implements syscalls, so the sandboxed program never talks to the real kernel. Stronger than containers, less overhead than a full VM. Used by Google (Agent Sandbox on GKE) and Modal. Tradeoff: not all syscalls are perfectly emulated, which can cause compatibility issues with some Linux software.

Level 3: Micro-VMs (Firecracker, Kata Containers, libkrun) Each workload gets its own kernel running on hardware virtualization (KVM). A kernel exploit inside one VM cannot reach the host or other VMs. This is the current gold standard for untrusted code. Firecracker boots in ~125ms with ~5MB memory overhead. Powers AWS Lambda, E2B, and Vercel Sandbox.

Level 4: Library OS (Microsoft LiteBox) Instead of filtering hundreds of syscalls, the application links directly against a minimal OS library that exposes only a handful of controlled primitives. Theoretically the thinnest isolation layer with the smallest attack surface. Experimental as of February 2026 — no SDK, no production usage.

Level 5: Confidential computing (AMD SEV-SNP, Intel TDX, OP-TEE) Hardware-encrypted memory isolation. Even the host OS and hypervisor cannot read the sandbox’s data. LiteBox is currently the only open-source tool in this comparison with a confidential computing runner (SEV-SNP). Relevant for regulated industries handling PII, financial data, or healthcare records.

The signal from the hyperscalers is unambiguous. AWS built Firecracker for Lambda. Google built gVisor for Search and Gmail. Azure uses Hyper-V for ephemeral agent sandboxes. Every one of them reached for their strongest isolation primitive and pointed it at AI. None of them reached for containers.

How to choose an AI agent sandboxing approach: four questions

Before you even look at Firecracker or Modal, you need to understand where your workload fits. The “right” tool depends entirely on your constraints around trust, latency, data, and compliance.

How untrusted is the agent code you run?

Security in 2026 isn’t binary. It’s a spectrum.

Internal logic: Running code your own engineers wrote that passed CI/CD? Standard containers (Layer 1 or 3) are probably fine.

LLM-generated code: Your agents generate Python to solve math problems or format data? The risk goes up significantly. You need strong isolation, either gVisor or MicroVMs, to prevent accidental resource exhaustion or logic bombs.

User-uploaded binaries/malicious agents: Allowing users or autonomous agents to execute arbitrary binaries or install unvetted PyPI packages? Assume the code is hostile. You need the strictest isolation available: hardware virtualization via MicroVMs (Firecracker) or air-gapped primitives.

The higher the risk, the lower in the stack you may need to build to control the blast radius.

How long do agent sessions need to run?

One-shot (inference/scripts): Quick script to generate a chart or run inference? Cold start time is your primary metric. You need sub-second snapshot restoration.

Long-running (agents): Agents maintaining state, “thinking” for minutes, or waiting for user input? Billing models become critical. Runtimes charging premium “per second” rates get expensive fast for sessions that idle. Managed platforms often provide better economics for duration. Building your own warm pools on primitives requires complex autoscaling logic to avoid paying for waste.

Do you have a data gravity problem?

Teams overlook this one all the time.

Small data payloads: Sending a few kilobytes of JSON and receiving text? Embeddable Runtimes (Layer 2) work great.

Large contexts/model weights: Loading 20GB model weights or processing a 5GB CSV? You’ve got a data gravity problem. Moving gigabytes of data into a remote sandbox API for every request creates massive latency penalties and egress cost nightmares. You need a Platform (Layer 3) where compute moves to the data, or a custom Layer 1 solution co-located with your storage.

What compliance and security requirements do you have?

The enterprise question: Selling to the Fortune 500? Need SOC 2 Type II or ISO 27001 certification immediately? Achieving those on a self-built “Primitive” stack takes 12 to 18 months of engineering effort and dedicated security personnel.

Auditability & data controls: Need granular audit logs for every system call? Strict data residency controls (guaranteeing code executes only in Frankfurt)? Managed platforms usually offer these as standard SKUs. Replicating this visibility in a DIY Firecracker fleet means building a custom observability pipeline that can penetrate the VM boundary without breaking isolation.

The three-layer AI agent sandboxing stack (primitives, runtimes, platforms)

Stop comparing Firecracker to Modal directly. They’re different categories solving different problems. In 2026, the ecosystem forms a hierarchy of abstraction.

Layer 1: The primitives (the “raw materials”). Open-source virtualization technologies you run on your own metal or EC2 bare metal instances. You become the cloud provider.

Examples: AWS Firecracker (MicroVMs), gVisor (User-space kernel), Cloud Hypervisor, and the new Microsoft LiteBox (Library OS).

Layer 2: The embeddable runtimes (the “APIs”). Middleware services that wrap primitives into a simple SDK. Sandboxing as a service for teams that need code execution without infrastructure management.

Examples: E2B, specialized code interpreter APIs, microsandbox.

Layer 3: The managed platforms (the “cloud”). End-to-end serverless compute environments. They handle the primitives, orchestration, scheduling, and scaling. The sandbox is the environment, not just a feature.

Examples: Modal, Northflank, and Daytona.

Layer 1 (primitives): benefits, trade-offs, and hidden costs

Layer 1 benefit: maximum isolation control

Layer 1 is where infrastructure companies and massive enterprises live. If you go this route, you’re building on AWS Firecracker, gVisor, or the experimental Microsoft LiteBox.

The promise? Absolute control. You define the guest kernel version. You control the network topology down to the byte. You can achieve the highest possible density by oversubscribing resources based on your specific workload patterns.

For teams building a competitor to AWS Lambda or a specialized vertical cloud, this is the only viable layer.

Layer 1 trade-off: you must build and operate the platform

But here’s the thing: “using” Firecracker is kind of a misnomer. You don’t just “use” Firecracker. You wrap it, orchestrate it, and debug it.

The operational reality of running primitives at scale reveals hidden engineering costs that can easily derail product roadmaps.

Image management: preventing thundering herd pulls

The hardest problem in sandboxing isn’t virtualization. It’s data movement.

To achieve sub-second start times for AI agents, you can’t run docker pull inside a microVM. You need a sophisticated block-level caching strategy.

When 1,000 agents start simultaneously (a “thundering herd”), asking your registry to serve 5GB container images to 1,000 nodes will capsize your network. You need lazy-loading technologies like SOCI (Seekable OCI) or eStargz.

Research shows that while SOCI can match standard startup times, unoptimized lazy loading can degrade startup performance. That means Airflow startup going from 5s to 25s. Building a global, high-throughput, content-addressable storage layer to feed your microVMs is a distributed systems challenge that rivals the sandbox itself.

Networking: TAP/TUN, CNI overhead, and startup latency

Networking kills microVM projects. Quietly.

Unlike Docker, which provides mature CNI plugins, Firecracker requires you to manually manage TAP interfaces, IP tables, and routing on the host.

Recent research (IMC ‘24) shows that at high concurrency (around 400 parallel starts), setting up CNI plugins and virtual switches becomes the primary bottleneck. This overhead can increase startup latency by as much as 263%, turning a 125ms VM boot into a multi-second delay.

And debugging networking inside a “jailer” constrained environment? Notoriously difficult. Standard observability tools often fail to penetrate the VM boundary.

Warm pools: cold-start mitigation vs. idle cost

Teams often maintain “warm pools” of pre-booted VMs to mitigate cold starts. This creates a complex economic problem.

Keep 500 VMs warm but only use 100? You’re burning cash on idle compute.

Building a predictive autoscaler that spins up VMs before a request hits, but not too many, is a serious data science challenge. In 2026, with GPU compute costs still high, the waste from inefficient warm pooling can easily exceed the markup charged by managed platforms.

LiteBox in 2026: what it is and when to use it

As of February 2026, Microsoft has introduced LiteBox, a Rust-based Library OS. It offers a compelling middle ground: lighter than a VM but with a drastically reduced host interface compared to containers.

While promising for its use of AMD SEV-SNP (Confidential Computing), LiteBox remains experimental. Unlike Firecracker, which has hardened AWS Lambda for years, LiteBox lacks a production ecosystem. Betting your company’s security on LiteBox today carries “bleeding edge” risk.

Google Agent Sandbox: the Kubernetes-native middle ground

Google’s Agent Sandbox deserves separate mention because it straddles Layer 1 and Layer 2. Launched at KubeCon NA 2025 as a CNCF project under Kubernetes SIG Apps, it’s an open-source controller that provides a declarative API for managing isolated, stateful sandbox pods on your own Kubernetes cluster.

What makes it interesting:

Dual isolation backends. Supports both gVisor (default) and Kata Containers, letting you choose isolation strength per workload.

Warm pool pre-provisioning. The SandboxWarmPool CRD maintains pre-booted pods, reducing cold start latency to sub-second — solving the warm pool problem discussed above without requiring you to build custom autoscaling logic.

Kubernetes-native abstractions. SandboxTemplate defines the environment blueprint. SandboxClaim lets frameworks like LangChain or Google’s ADK request execution environments declaratively. This is infrastructure-as-YAML, not infrastructure-as-code.

No vendor lock-in. Runs on any Kubernetes cluster, not just GKE. Though GKE offers managed gVisor integration and pod snapshots for faster resume.

The tradeoff: you still operate the Kubernetes cluster. This isn’t zero-ops like Layer 3 platforms. But for teams already running on Kubernetes who need agent sandboxing without adding a new vendor dependency, Agent Sandbox eliminates most of the DIY orchestration work described in the sections above while keeping you on open infrastructure.

If you’re on GKE already, this should be your first evaluation before looking at managed platforms.

Layer 2 (embeddable runtimes): sandboxing as an API

What “sandboxing as an API” means

Layer 2 solutions wrap isolation primitives into developer-friendly interfaces. E2B takes the “Stripe for Sandboxing” approach with a managed API, while microsandbox offers the same micro-VM isolation tier as a self-hosted runtime. They abstract Layer 1’s complexities (managing Firecracker, TAP interfaces, root filesystems) into a clean SDK.

This layer works best for SaaS teams that need to add a “Code Interpreter” feature quickly. We’re talking days, not months.

microsandbox: the self-hosted alternative

Not every team wants to send code to a third-party API. microsandbox takes a different approach from E2B: it’s a self-hosted, open-source runtime that provides micro-VM isolation using libkrun (a library-based KVM virtualizer). Each sandbox gets its own dedicated kernel — hardware-level isolation, not just syscall interception — with sub-200ms startup times.

The key difference from E2B: microsandbox runs entirely on your infrastructure. No SaaS dependency, no data leaving your network. This makes it the stronger choice for teams with strict data residency requirements or air-gapped environments where a cloud sandbox API isn’t an option.

The tradeoff is predictable: you own the ops. microsandbox gives you the isolation primitive and a server to manage it, but you handle scaling, monitoring, and image management yourself. Think of it as the “self-hosted E2B” — same security tier (micro-VM), different operational model.

As of early 2026, microsandbox has approximately 4,700 GitHub stars and is licensed under Apache 2.0. It’s the most mature open-source option in this layer for teams that need to self-host.

Layer 2 against the four questions (security, duration, data gravity, GPUs)

Untrusted Code: Layer 2 excels here. Vendors purpose-built these runtimes for executing LLM-generated code. E2B uses Firecracker; microsandbox uses libkrun. Both provide hardware-level isolation with dedicated kernels per sandbox.

Session Length: This layer optimizes for ephemeral, one-shot tasks. Agent needs to run a Python script to visualize a dataset and then die? Cost-effective. But for long-running agents that persist for minutes or hours, the per-second billing models common here accumulate rapidly, often exceeding raw compute costs.

Data Gravity: Data movement is the main architectural constraint at this layer, but it affects managed and self-hosted runtimes differently. For managed APIs like E2B, small payloads (JSON, spreadsheets, short scripts) travel over the network with negligible overhead. E2B supports volume mounts and persistent storage, which extends its range to moderate-sized datasets. microsandbox sidesteps the network hop entirely — since it runs on your infrastructure, sandboxes execute co-located with your data by definition, eliminating egress costs and transfer latency. The breakpoint: once individual executions routinely move multi-gigabyte files (large model weights, video processing, dataset joins), even volume mounts can’t fully mask the I/O penalty on managed APIs. At that scale, either self-host with microsandbox, move to Layer 3 where compute and storage share an internal network, or build a co-located Layer 1 solution.

GPU Access: GPU support in Layer 2 runtimes is still maturing. E2B currently focuses on CPU workloads. If your agents need GPU inference or fine-tuning, this is a genuine gap that may push you toward Layer 3 platforms or a custom Layer 1 build with GPU passthrough.

Layer 3 (managed platforms): serverless sandboxing for agents

Why managed platforms unify compute, data, and isolation

Managed Platforms take the “Serverless Cloud” approach. The platform is the sandbox.

You don’t make an API call to a separate sandbox service. Your entire workload runs inside an isolated environment by default. This unification solves the friction between code, data, and compute.

Three managed platforms stand out, each with a different architectural bet:

Modal uses gVisor (user-space kernel isolation) optimized for Python ML workloads. Strengths: native GPU support (T4 through H200), serverless autoscaling from zero, infrastructure-as-code via Python SDK. Limitations: gVisor-only isolation (no microVM option for higher-security requirements), Python-centric (limited multi-language support), no BYOC or on-prem deployment, SDK-defined images create migration friction.

Northflank uses both Kata Containers (microVM) and gVisor, selecting isolation level per workload. Strengths: strongest isolation of the three (dedicated kernel via Kata), BYOC deployment (AWS, GCP, Azure, bare metal), unlimited session duration, GPU support with all-inclusive pricing, OCI-compatible (no proprietary image format). Limitations: more comprehensive platform means steeper initial setup than a pure sandbox API, less Python-specific DX than Modal.

Daytona uses Docker containers by default with optional Kata Containers for stronger isolation. Strengths: fastest cold starts in the market (sub-90ms), native Docker compatibility, stateful sandboxes with LSP support, desktop environments for computer-use agents. Limitations: default Docker isolation is the weakest of the three — you must explicitly opt into Kata for microVM-level security. Younger platform (pivoted to AI sandboxes in early 2025).

Layer 3 against the four questions (security, data gravity, GPUs, compliance)

Untrusted Code: Platforms provide default isolation, but the level of protection varies. Modal uses gVisor, which intercepts syscalls in user space — stronger than containers but not equivalent to a dedicated kernel. Northflank offers Kata Containers (full microVMs with dedicated kernels) for workloads that require the strictest isolation. Daytona defaults to Docker containers, which may be insufficient for truly hostile code unless you explicitly configure Kata. If your threat model assumes kernel exploits, ask whether the platform offers microVM-level isolation, not just “sandboxing.”

Data Gravity: Layer 3 platforms generally solve data gravity by co-locating compute and storage on high-speed internal networks, avoiding the upload/download penalty of Layer 2 APIs. Modal and Northflank both support volume mounts and cached datasets. However, data residency varies: Northflank offers BYOC deployment guaranteeing data stays in your VPC, while Modal runs on their managed infrastructure. If regulatory requirements dictate where data physically resides, BYOC support becomes a deciding factor.

GPUs on demand: scheduling and isolation for multi-tenant inference GPU access is the clearest Layer 3 differentiator, but support varies. Modal offers the broadest GPU selection (T4 through H200) with per-second billing, though total costs add up when you factor in separate charges for GPU, CPU, and RAM. Northflank offers GPU support with all-inclusive pricing that can be significantly cheaper for sustained workloads. Daytona currently lacks GPU support.

Research shows that without strict hardware partitioning (like MIG), multi-tenant GPU workloads can suffer 55-145% latency degradation. Managed platforms handle this scheduling complexity, offering “soft” or “hard” GPU isolation and handling the drivers, CUDA versions, and hardware abstraction. You request a GPU in code (e.g., gpu=”A100”), and the platform handles physical provisioning and isolation.

Compliance: Enterprise compliance features vary significantly across platforms. Managed platforms generally let you inherit controls faster than building on primitives, but the specifics matter. Northflank’s BYOC model lets you keep your data in your own cloud account, simplifying compliance with data residency requirements. Modal’s managed-only infrastructure means your data runs on their servers. Daytona offers self-hosted options. Evaluate each vendor’s SOC 2 certification status, audit log granularity, and network isolation capabilities against your specific compliance requirements.

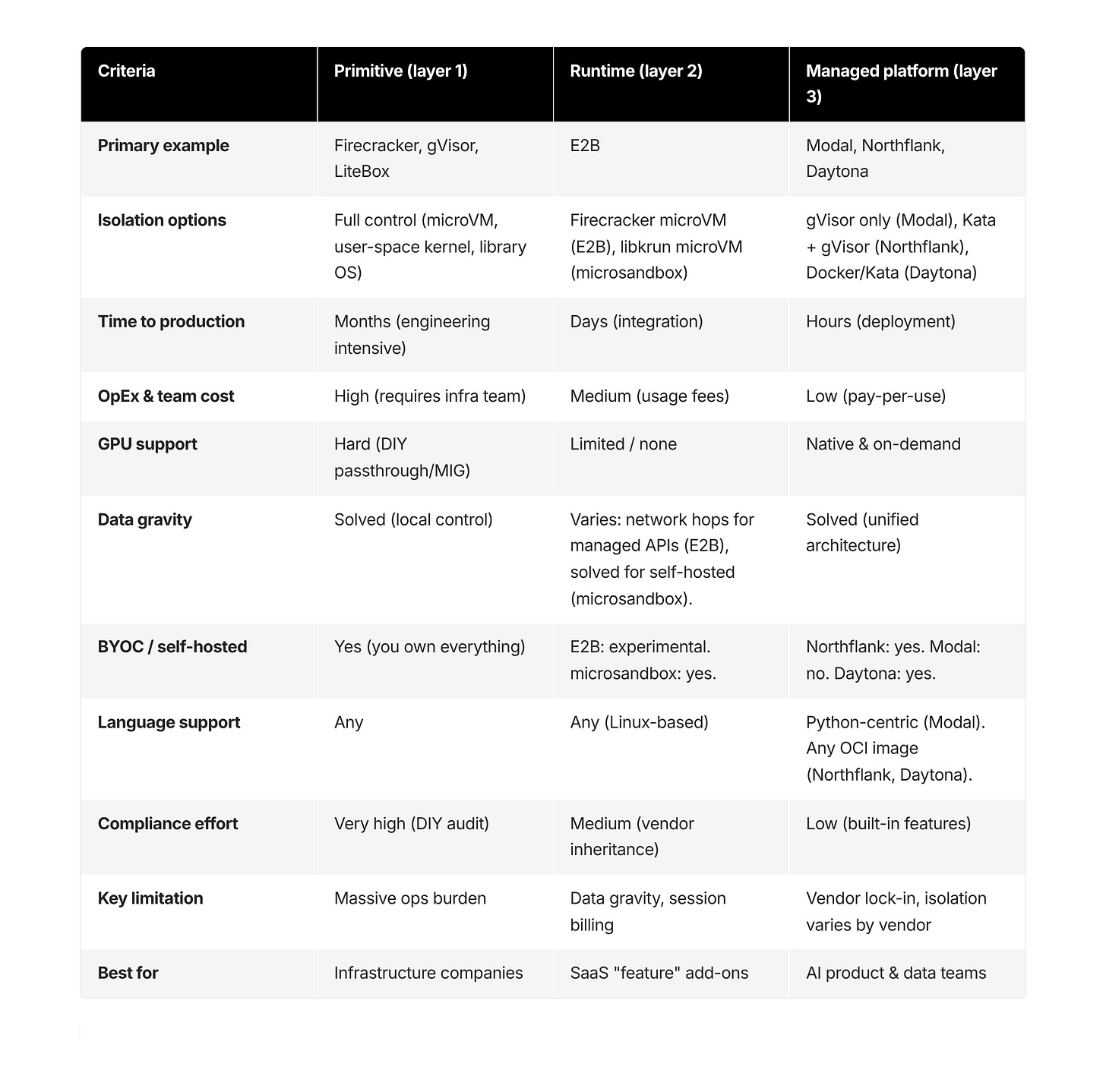

Comparison: primitives vs. runtimes vs. managed platforms

Notable hybrid: Google Agent Sandbox. K8s-native controller supporting gVisor + Kata with warm pools. Runs on your cluster. Open-source (CNCF). Best for teams already on Kubernetes.

What’s next in AI agent sandboxing (2026–2027)

Looking toward late 2026 and 2027, three trends will reshape this stack.

Trend: library OS sandboxes (LiteBox)

Microsoft’s entry with LiteBox validates the move toward Library Operating Systems. By bundling application code with only the minimal kernel components needed (using a “North/South” interface paradigm), Library OSs promise the low overhead of a process with the isolation of a VM.

Still experimental now. But this could redefine the performance/security trade-off in 2-3 years, potentially replacing containers for high-security workloads.

Trend: daemonless, embeddable sandboxing (BoxLite)

The next frontier is sandboxing without any server process. Projects like BoxLite (distinct from Microsoft’s LiteBox) explore embedding micro-VM isolation directly into an application as a library — no daemon, no daemon socket, no background process. Where microsandbox runs as a server you deploy, BoxLite aims to be a library you import.

Think of it as the difference between PostgreSQL (a server) and SQLite (a library). BoxLite is the SQLite model applied to sandboxing: a single function call spins up an isolated OCI container inside your application process. This serves the “local-first” AI agent movement, where agents run on developer machines or edge devices without cloud dependencies.

Still early (v0.5.10, 14 contributors, ~1000 GitHub stars), but the architectural direction — sandboxing as an embedded library rather than a service — could reshape how lightweight agent frameworks handle isolation.

Trend: protocol-level permissions with MCP

Security is moving up the stack. Kernel-level isolation answers the question “can this code escape the sandbox?” but not “should this agent be allowed to make HTTP requests at all?” The Model Context Protocol (MCP) opens the door to enforcing permissions at the protocol layer, where agent capabilities are declared rather than inferred.

Here’s the mechanism. An MCP server exposes a manifest of tools — web_search, filesystem_read, database_query — each with a defined scope. A sandbox runtime that understands MCP can derive its security policy directly from that manifest. An agent authorized to use web_search gets outbound HTTPS on port 443. An agent with only filesystem_read gets no network access at all. File system mounts narrow to the specific paths the tool declares. The sandbox’s firewall rules and mount points become a function of the agent’s tool permissions, not a static configuration an engineer writes once and forgets.

No production sandbox does this today. But the primitives are converging: MCP adoption is accelerating across agent frameworks (LangChain, CrewAI, Google ADK all support it), and sandbox runtimes already expose the network and filesystem controls needed to enforce these policies programmatically. The missing piece is the glue layer that translates an MCP tool manifest into a sandbox security policy at boot time. Expect the first integrations in late 2026.

Conclusion: choosing the right sandbox layer for your AI agents

The 2026 sandbox landscape isn’t about choosing a virtualization technology. It’s about choosing your level of abstraction. The defining question for engineering leadership is: Where do you create value?

If your core business is selling infrastructure — building the next Vercel or a specialized vertical cloud — you must build on primitives (Layer 1). The operational pain of managing Firecracker fleets is your competitive moat.

If you need to add code execution as a feature inside an existing product, embeddable runtimes (Layer 2) get you there in days with strong isolation and minimal architecture changes.

If your core business is building an AI application, agent, or data pipeline, managed platforms (Layer 3) trade control for velocity. But “managed” is not a monolith — evaluate isolation strength (gVisor vs. microVM), deployment model (managed vs. BYOC), language constraints, and session economics for your specific workload before committing.

The one decision you shouldn’t make in 2026: running untrusted AI-generated code inside shared-kernel containers and hoping for the best. The cloud providers have already told you that’s not enough. Listen to them.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Is docker (runc) safe enough to run untrusted AI agent code?

For hostile or user-supplied code, shared-kernel containers generally don’t provide sufficient isolation. Use stronger boundaries, such as microVMs (e.g., Firecracker) or hardened user-space kernels (e.g., gVisor), or run on a managed platform that provides multi-tenant isolation by default.

What’s the difference between firecracker and gVisor for sandboxing?

Firecracker uses hardware virtualization (microVMs) for stronger isolation, but this typically introduces more operational complexity. gVisor intercepts syscalls with a user-space kernel for improved isolation over standard containers, often with easier integration but at the cost of different performance/compatibility trade-offs.

When should I choose a primitive vs an embeddable runtime vs a managed platform?

Choose primitives when you need maximum control and can operate the fleet (scheduler, images, networking, compliance). Choose an embeddable runtime when you need to add code execution fast, and payloads are small. Choose a managed platform when you need GPUs, data-local execution, and minimal ops.

What is “data gravity” and why does it matter for sandboxing?

Data gravity is the cost and latency of moving large datasets or model weights to where code runs. If you’re routinely moving gigabytes per execution, API-style sandboxes become slow and expensive. Platforms or co-located primitives reduce transfers by running compute near the data.

Are embeddable sandbox APIs (layer 2) good for long-running agents?

Vendors usually optimize them for short-lived, one-shot execution. For agents that idle or run for minutes/hours, per-second billing and session management can get expensive compared to a platform or a self-managed fleet.

Do I need GPU isolation for AI agents, and how is it handled?

If multiple tenants share GPUs, “noisy neighbor” effects can cause unpredictable latency and security concerns. Managed platforms typically handle GPU scheduling and isolation (e.g., MIG/partitioning strategies), whereas DIY approaches require significant engineering effort.

What operational work do I take on if I build on firecracker (layer 1)?

You own image distribution/caching, networking (TAP/TUN, routing), orchestration, warm pools, autoscaling, observability, and incident response. The isolation primitive is only one part of running a production sandbox fleet.

What is litebox and is it production-ready in 2026?

LiteBox is a Library OS approach that reduces the host interface compared to containers. As described, it remains experimental relative to battle-tested microVM approaches, so adopting it carries higher risk unless you can tolerate bleeding-edge dependencies.

How do I think about compliance (SOC 2, ISO 27001) when choosing a sandbox layer?

Building compliance on primitives typically requires substantial time and dedicated security engineering. Managed platforms can let you inherit controls (audit logs, network boundaries, residency options) faster, depending on vendor capabilities and your requirements.

What cold start time should I expect from modern sandboxes?

Many modern approaches can achieve sub-second starts with snapshots and caching. But real-world latency often depends more on image distribution, networking setup, and warm pool strategy than on the isolation primitive alone.